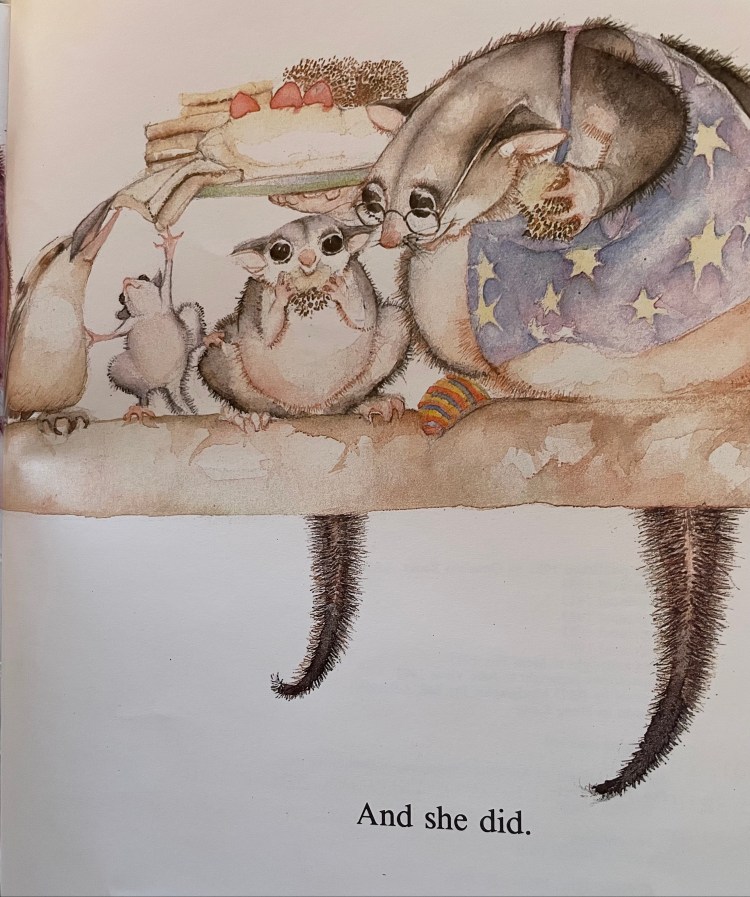

From that time onwards Hush was visible. But once a year, on her birthday, she and Grandma Poss ate a vegemite sandwich, a piece of pavlova and a half a lamington, just to make sure that Hush stayed visible forever.

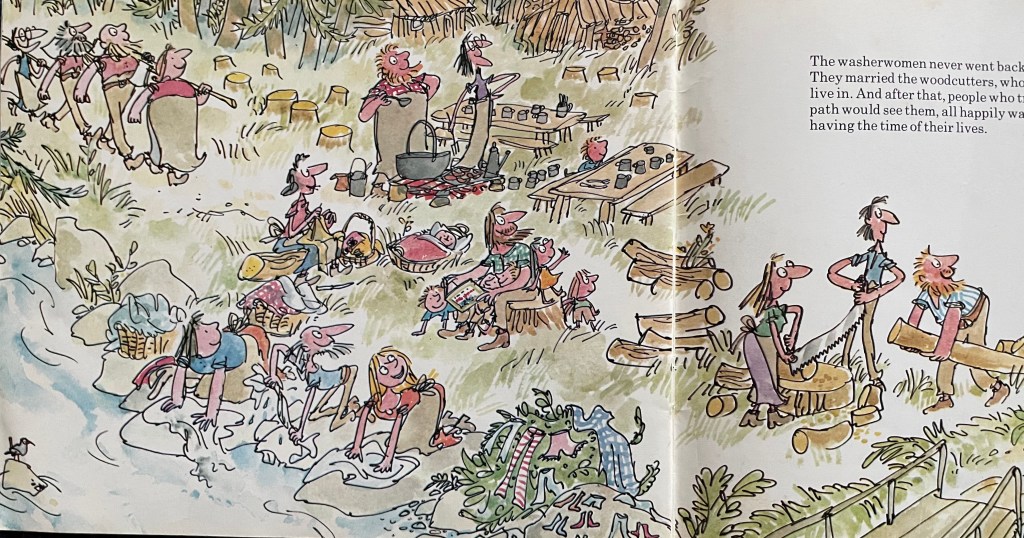

Julie Vivas’s watercoloured scenes and characters exist in white space, anchored by the horizontal lines of branches, verandah rails and a school bench. Grandma Poss performs her bush magic in a star-covered pinny and stripey slippers. Her specs are another signifier of her wisdom, even if she can’t find the spell she needs in her many books (she’s finally discarded them for this final picture.)

Hush happily makes gooey-eyed contact with the reader as she demolishes half a lamington to ensure her visibility ever after. Many suburban Australians have seen this look before, as a real live possum is surprised with the first fruit of the season in a cherished backyard tree. Grandma holds the plate with the other birthday goodies aloft and the kookaburra levers a vegemite sandwich into gulping position. In between them, a possum joey reaches up. This little unnamed character has hitched a ride from Perth to Tasmania on the last leg to be in on the feast.

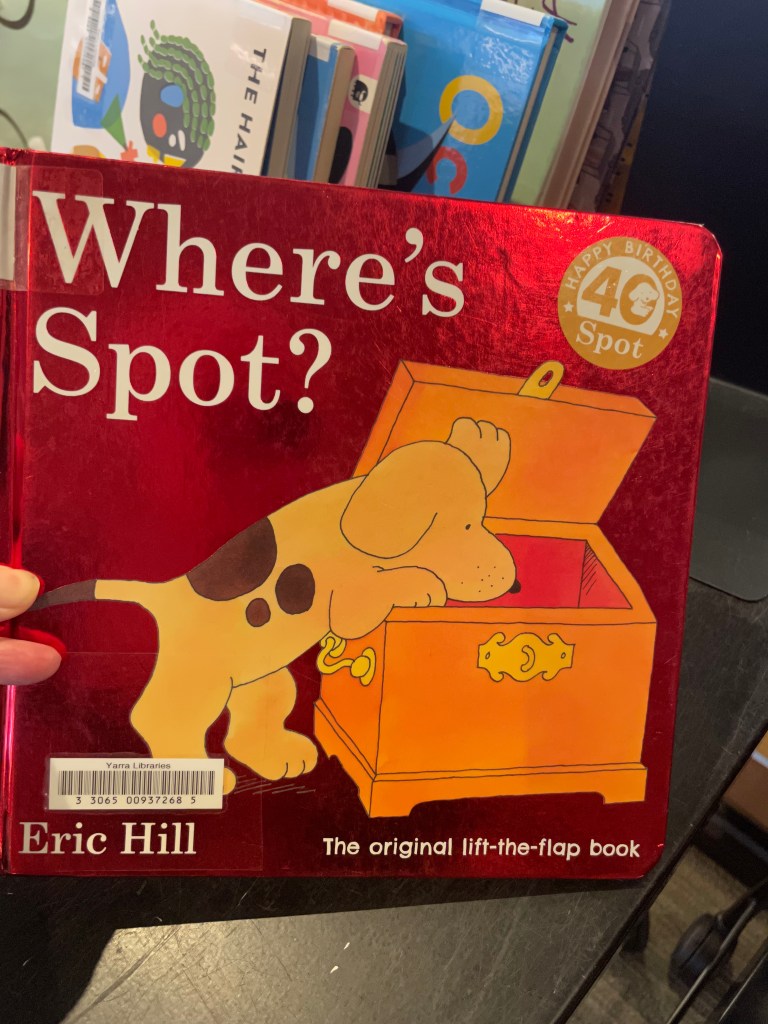

Vivas’s airy line and delicate detail, with a naturalistic palette for the bush scenes, ensured this book’s international and ongoing success. Mem Fox has written about its history on her website, and the book was recently reissued in the now customary 40th birthday edition.

In 1983 I moved up from being the Assistant Children’s Librarian to the Children’s Librarian position at St Kilda Library. I had finally finished my library qualifications at RMIT : without distinction, so I was not invited to do the fourth year to convert my diploma into a degree. This meant I couldn’t formally study Children’s Literature. Poor me – back to reading everything on the trolley, instead.

Visiting local schools to promote the library and get kids excited for Children’s Book Week, I read this book aloud over and over. The format and design of this book made it perfect for sharing with a group. Teachers went ga-ga over it, and the dynamics of this experience emboldened me to be brave enough to sing a line of the text : “Here we go round the Lamington Plate” begged for it.

Here are some photos of the library, as it is in 2023.

The Children’s Library was at the front of the building at the time, with its distinctive lights visible from Carlisle Street. I like the reflection of the St Kilda Town Hall in this shot, and the Number 3 tram that took me home.

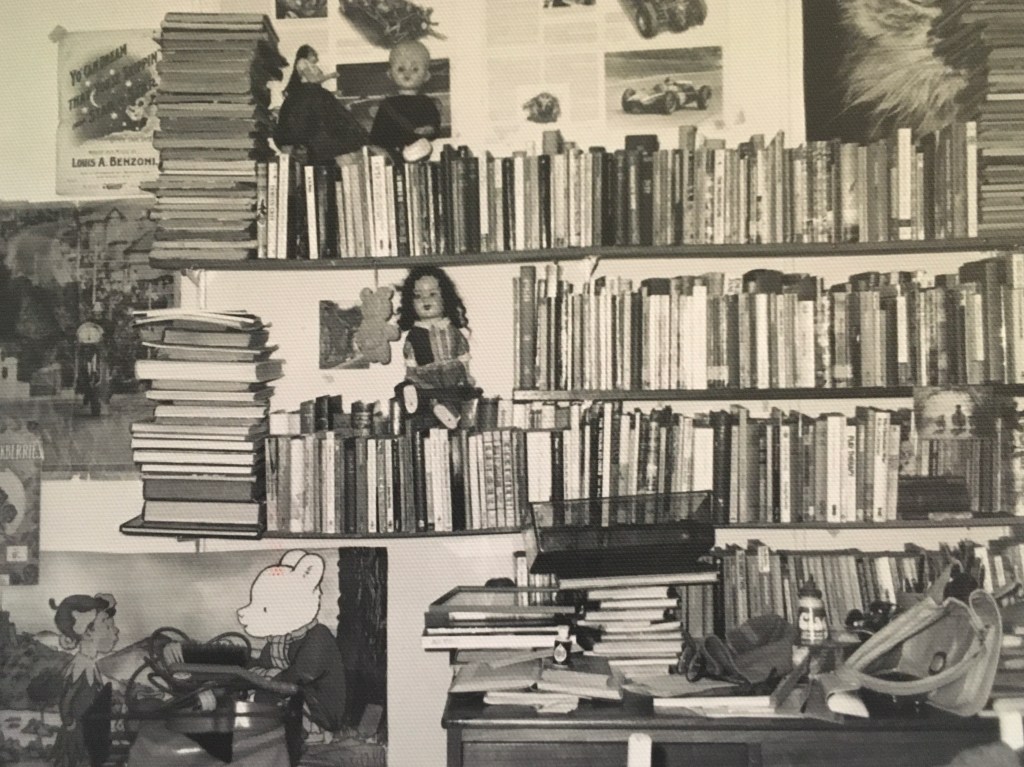

I found this photograph on the 50th anniversary gallery on Port Phillip Libraries’s site today.

The kids’ collection has now moved to the rear of the building but I’m so happy to see the original timber face-out shelving is still in use. On the day I visited earlier this year, I noted the copy of Marcia Brown’s Stone Soup which I remember as another storytelling favourite. Eating never fails as a theme in picture books.

Now look back at the black-and-white photo – the shelf at the bottom, near the middle ? Spooky.

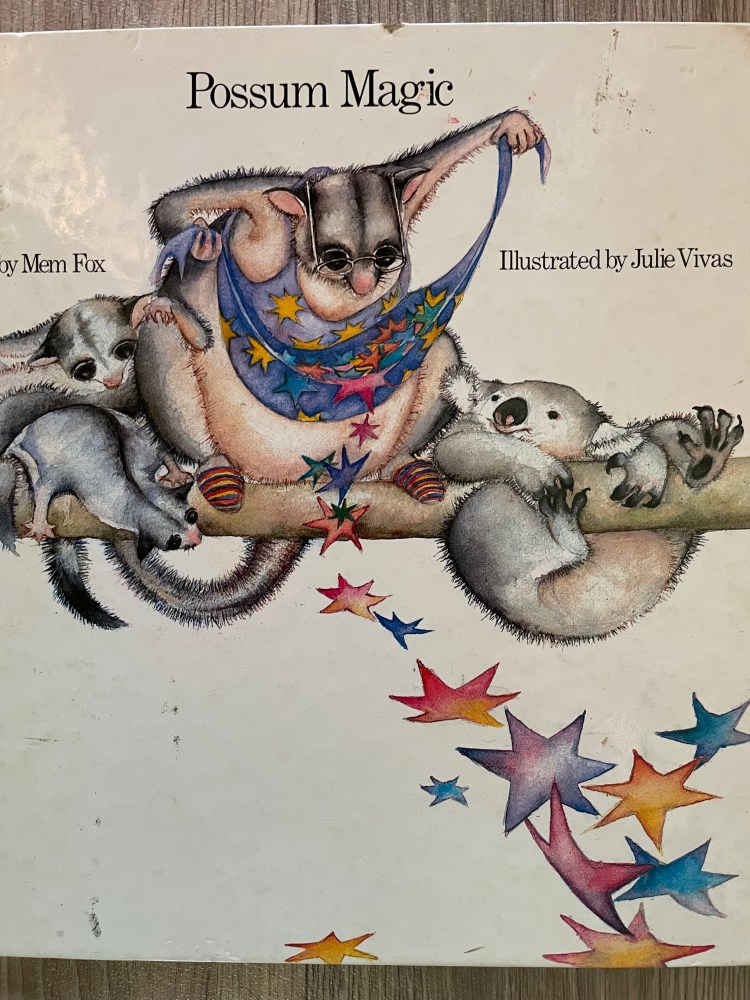

I had joined the Children’s Book Council of Australia and was in the Essendon Town Hall the night that the Children’s Book of the Year awards were announced.

There was palpable disbelief among teacher and librarian members present that Pamela Allen’s Bertie and the Bear had beaten Possum Magic. My friend and mentor, Margaret Aitken, was the Victorian judge that year, and she thought that she would have to hide in the toilets to escape their ire.

Maybe that’s why it would be another twenty two years before I became a judge myself.