Tricksters use their wits instead of their fists to outsmart more powerful opponents. Stories about these wily characters are told all over the nation.

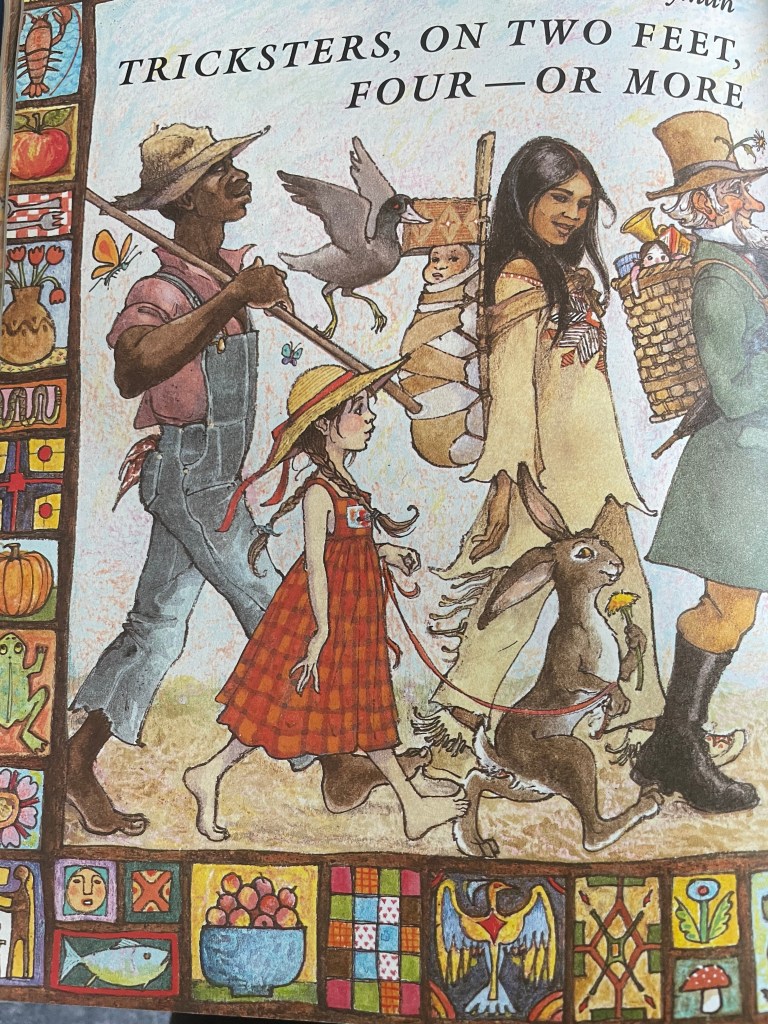

The cropper who drove a hard bargain keeps his hoe at the ready, and his head up. A woman of the Mohican carries the god Wasis on her back while keeping an eye on that scamp Brer Rabbit. He gives the reader the side-eye as he leads (or is led by) Mr Man’s little girl – and is that Uncle Sam hefting a pedlar’s pack? The mud hen who defeated Iktome flies in to join the parade, continued across a double spread in a wonderful invitation to the stories beyond.

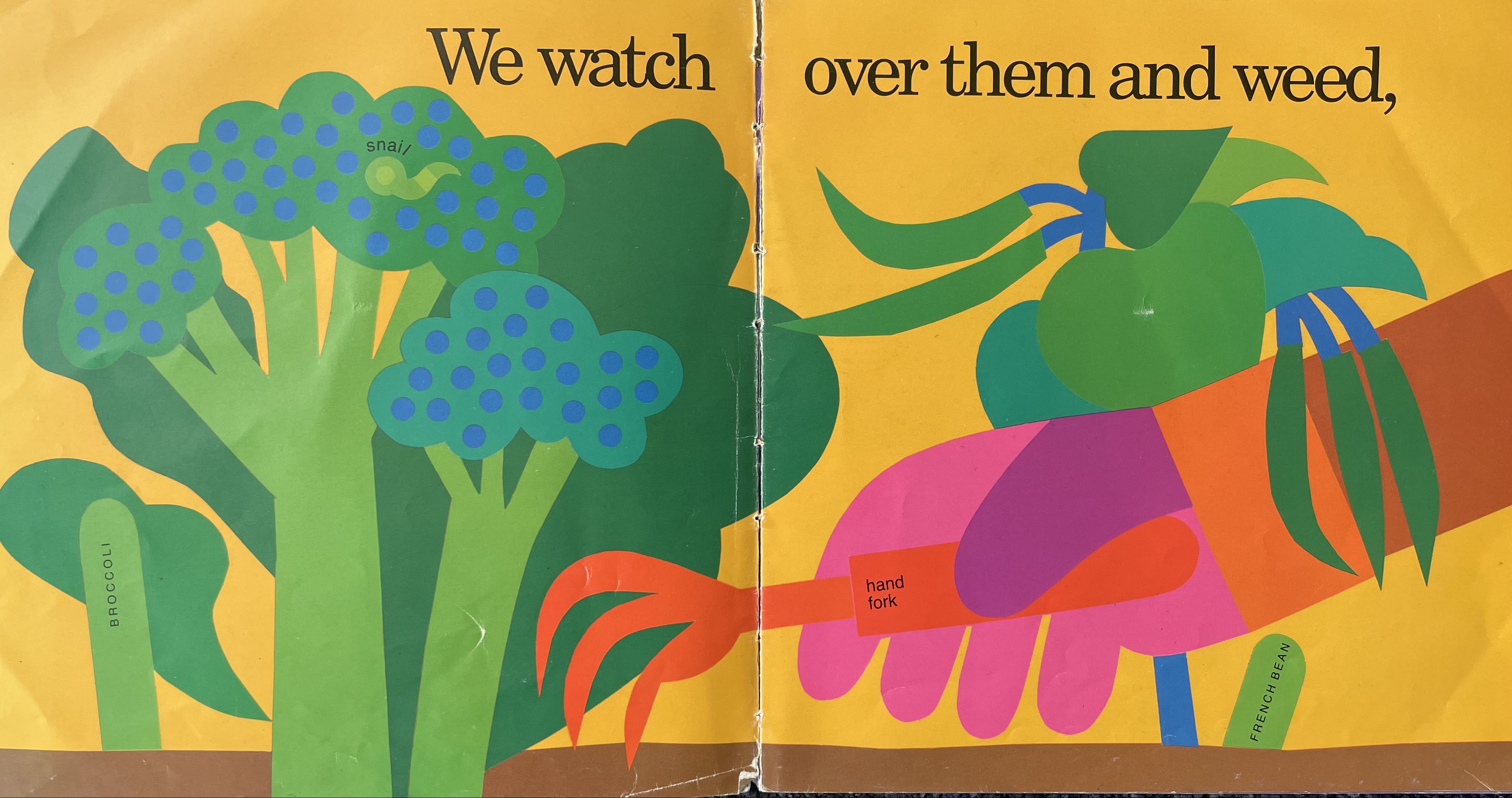

Who would give a 398 page book as a baby gift? Only someone who truly understood the importance of starting booksharing as beauty appreciation. It’s impossible to write about all of the artists represented so I’ll do as the format dictates, and as my children showed me: page through and pick the one I love best (today).

Trina Schart Hyman used firm pencil outlines for these fresh interesting characters which she then filled with watercolour wash. The superb shading suggests the dust of the open road, and the figures are all gesture and action – who doesn’t want to follow them wherever they’re going? TSH as a designer knew how to pack a page with visual interest for a child to pore over. This chapter is enlivened by superb page decorations that blend the features of adobe and cabin walls, merchant signage and mythological symbols into a gorgeous quilt patch border. I first met her work at St Kilda Library, where we subscribed to Cricket magazine – hard to say if I was first exposed to TSH’s work there, or in her many many illustrated books across genres. I do know that seeing any of her work today lifts the heart in the way it first did in 1977.

Jackie is an intuitive children’s librarian, former columnist for School Library Journal, coordinator of a fun-filled Picture Book Group … and splendid book chooser. We went together to the New York Public Library to hear Dorothy Butler speak in 1989 – with the size of the Fairfax County Library system and staff, we didn’t have the chance before that to get to know each other. Those couple of days were all it took for a lifetime of friendship since.

From 1993, she and her husband Alan began visiting Australia annually, so that he could teach in Canberra, and they somehow managed flying visits to Melbourne, and later Perth, as part of those trips.

The gifts – not just books – that they gave my family during that time will never be forgotten. (It was Alan who first called my son Big Bob.)

Jackie took this picture of me with Big Bob in 1993 outside her favourite Melbourne bookstore, the legendary Little Bookroom which I’ve written about elsewhere on this blog.

This book gave me a dazzling gallery of twentieth century picture book illustrators, a valuable touchstone for me once I was a fulltime parent and no longer saw new books daily.

Ms May recently paged through it with me, showing me which stories and pictures she loved, which she passed over with indifference, and the aspects of her favourite pages. The beauty of a large collection like this one can’t be underestimated. Thank you, dear Jackie and Alan.

The roll call of featured artists includes Marcia Brown – she was 75 at the time. Here’s good old Sal, as painted by her.