Hi! I’m the bus driver. Listen, I’ve got to leave for a little while, so can you watch things for me until I get back? Thanks. Oh and remember:

Don’t let the pigeon drive the bus!

On a Saturday night in March of 2003, there was an unusually severe windy rainstorm in Perth. The wind drove the rain under the roof of the Nedlands Library, where it dripped through the ceiling of the children’s room. By the time the damage was discovered on Sunday afternoon, the carpet was still underwater and 80% of the books were damp to wringing wet. There was some roof leaks in the main library as well.

The library closed for a week-long clean up. After assessment from the State Library of WA – most of the stock belonged to them – the books were removed as soon as possible to prevent the danger of spread of mould. Throwing them into a trailer to be taken to the council depot reduced everyone to tears.

About 70% of a library’s stock is out on loan at any one time, so the collection was not devastated completely. We were offered additional books from State Library of WA, as well as very generous community donations from residents, the Children’s Book Council of WA and booksellers. A small children’s library space was established at the other end of the building during the refurbishment of the room which took about 9 months. Storytime was suspended for a time.

As always I turned to picture books for comfort and relief, and so this was Mo Willems’ moment.

Willems read comics growing up, he tells young fans. He learned from them how to action-pack a square, using a character made of a few lines.

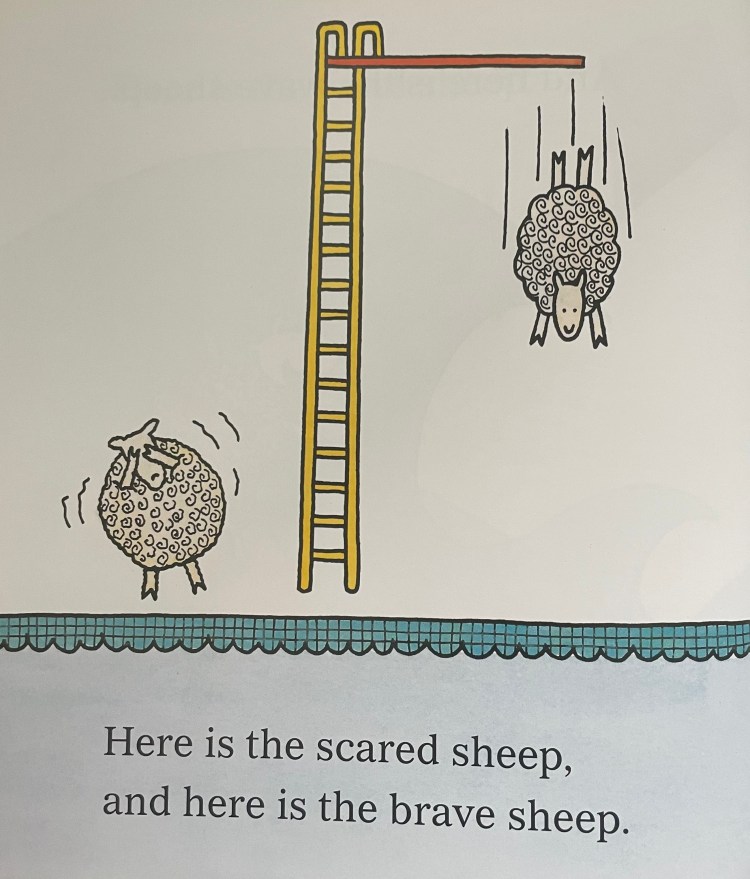

Many writers of picture books have their protagonist address the reader directly but Willems’s pigeon is in a class of its own. Enlisted by the bus driver with the request that is the title, readers are fascinated to see and hear the bird’s requests, sweet-talk, confidence, pleading and the final feathery tantrum. Willems’ design and use of speech bubbles is perfectly placed to keep the pages turning.

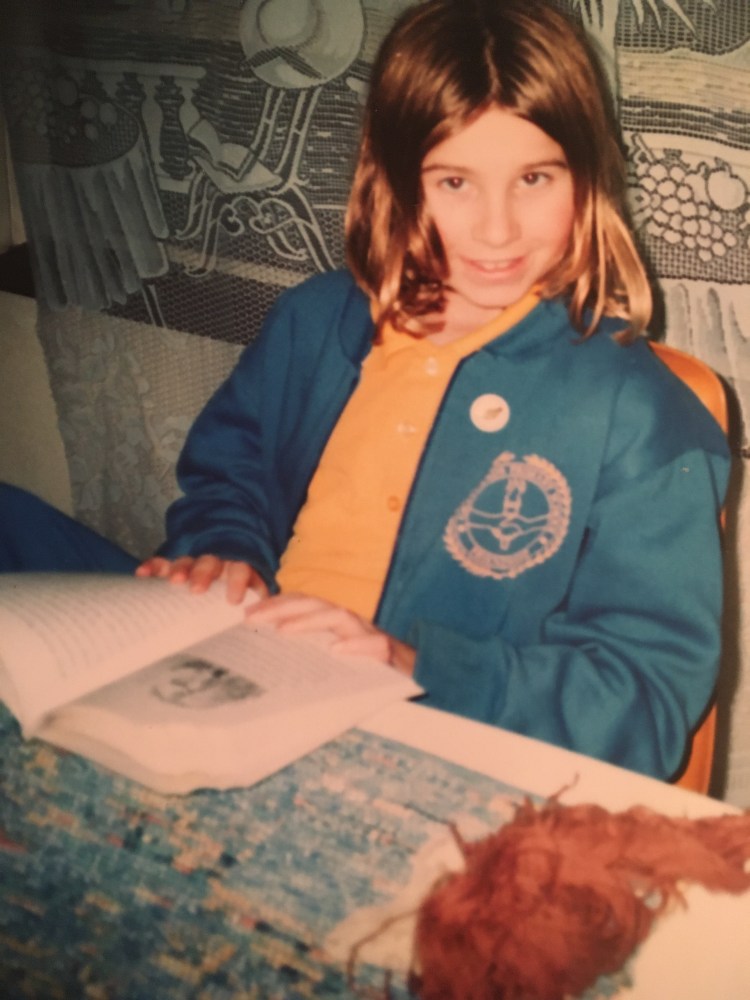

I’ve been reading and enjoying comic strips long before the 40 years began. My father stuck funny cartoons on the wall of the smallest room in the house. My parents never said what I could and couldn’t read so I regularly took Dad’s copy of Sick, Sick, Sick by Jules Feiffer from his bookshelf, even though I definitely did not understand most of it.

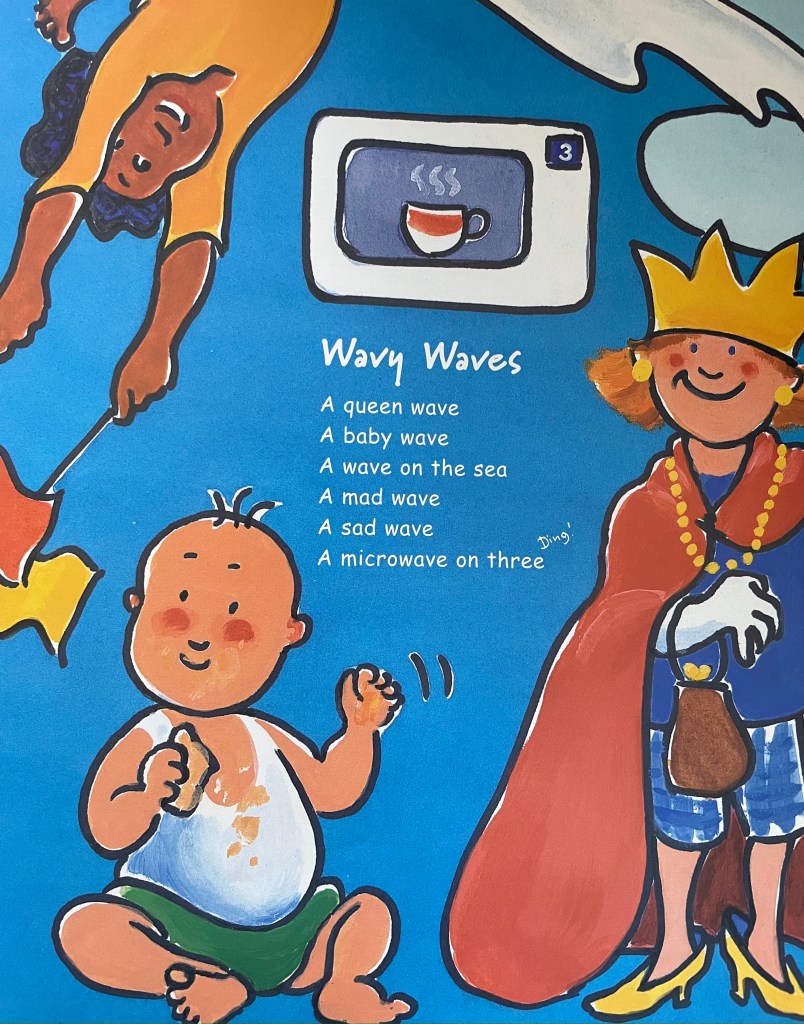

Princess was my weekly magazine and I was ‘getting’ these jokes in 1967.

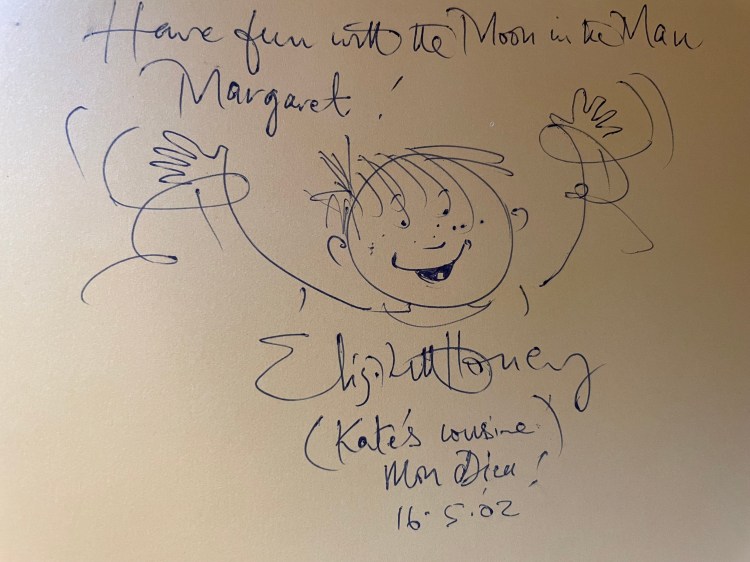

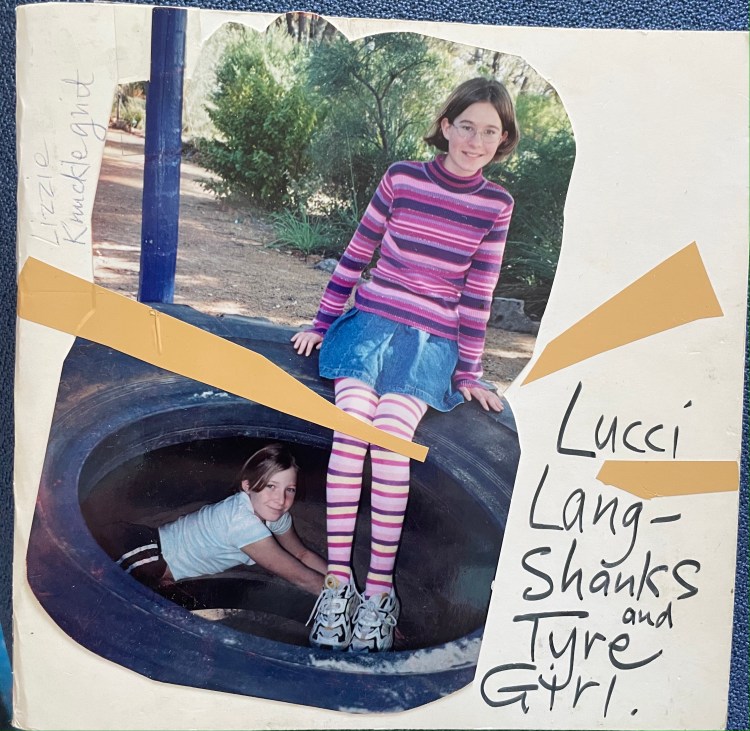

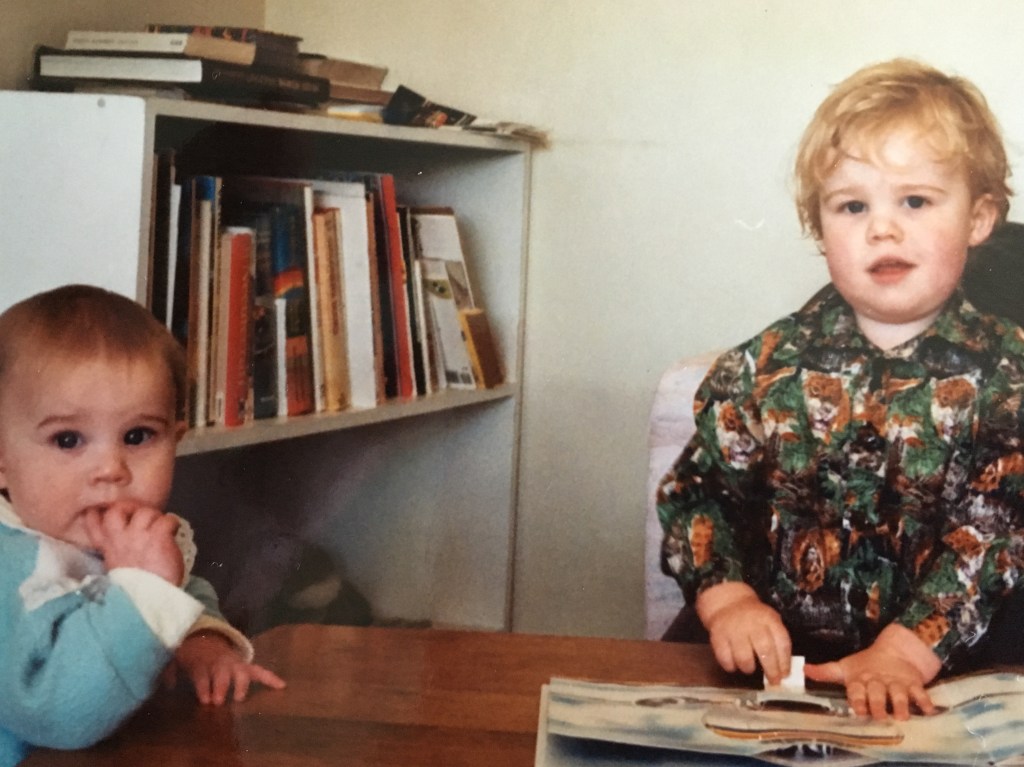

Ms May had moved primary schools at the start of 2003, to be close to where I worked. Students would come to Mt Claremont Library from the school and it was probably during one of these visits with her Year 4 class she heard me read Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! for the first time. (As this picture shows, she had moved on to chapter books as an independent reader, so we weren’t sharing many picture books together.) She remembers that she ‘had never heard a book as funny as that.’ She had not yet discovered my Princess annuals.

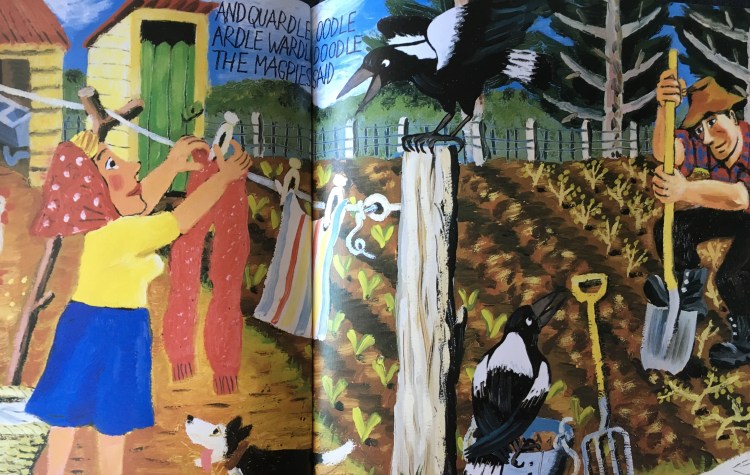

Ms May was taught by the excellent Mrs Ryan, who signed everyone up to the Gould League. To this day, she knows a wood duck from a mountain duck – and we recently enjoyed Mo Willems’ draw-along together, so the pigeon lives on.

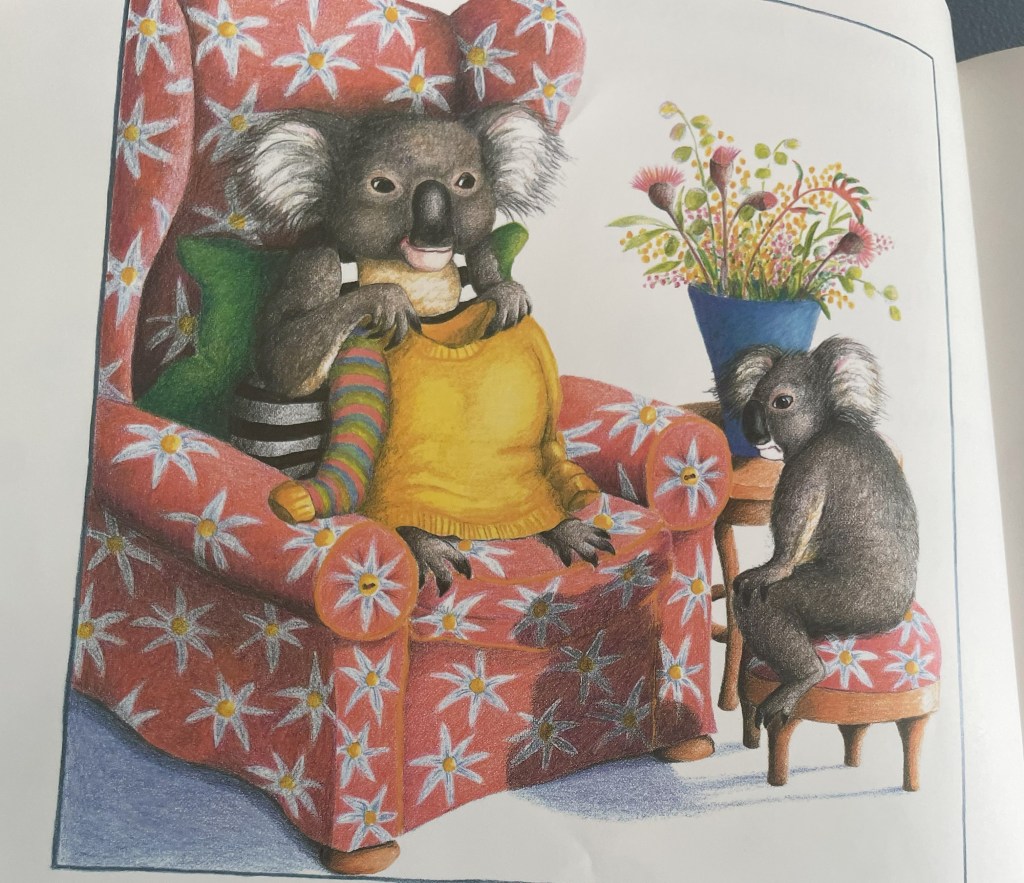

I must have shown too much enthusiasm for it among colleagues in later years – happy birthday to me!