Year 1 of 40

‘This is our land. It goes back, a long way back, into the Dreamtime, into the land of our Dreaming.’

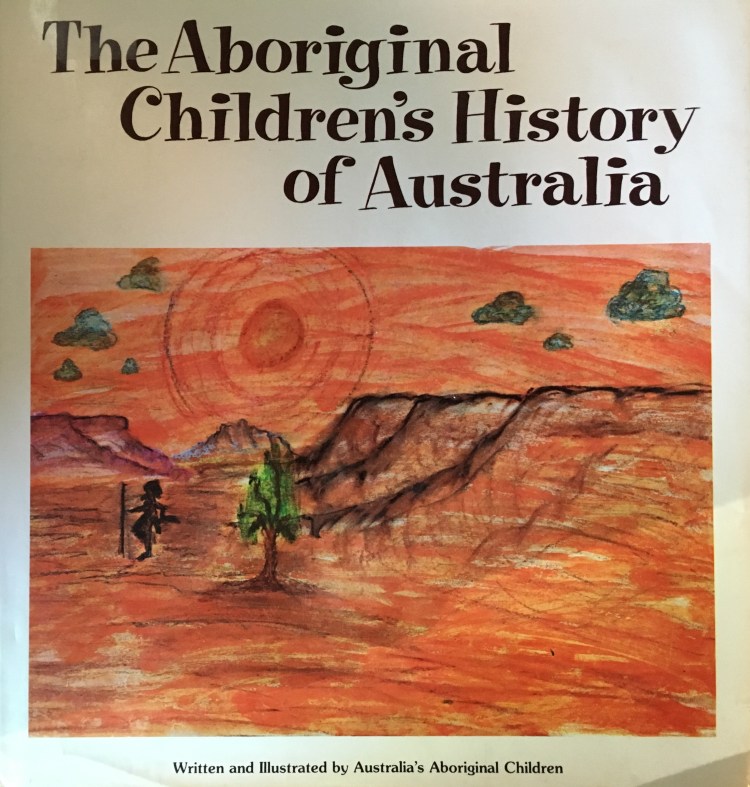

In paintings, drawings in texta and pencil, children from communities all over Australia tell stories from their world in the late 1970s, and times past. The format of the book is very much that of art books of the period, and the works have a high standard of reproduction which honours the children’s work. As well as historical subjects, the young writers tell stories of their ordinary life in a way that relates universal childhood experiences.

Alex Ronan of Perth tells the story of Whadjuk Noongar man Yagan on page 62 of this book:

“Yagan made friends with [the white men] but they made war…This got worse and worse until Yagan and his dad were killed.

The mother cried.”

Cultural historian Dr Mary Tomsic says, “Children’s voices, as expressed in books by children, are a significant but underutilised cultural and historical source that records children’s experiences and interpretation.”

Interactions with visitors and invaders – Captain Cook, white settlers and the Japanese during World War II – are retold in detail, as is the activism at Wave Hill. Bloody conflict and suffering are not avoided but neither are they sensationalised.

The artist of individual paintings in the book are identified by their community and state in captions. (Heartbreakingly, there is more than one labelled Artist Deceased.) It’s not always clear whether the story on the same page or spread has also been written by that child, but there is a list of the story-tellers by name at the start of the book.

In an article published by Northern Land Council on January 23 2019, Yolnu author and artist Merrkiyawuy Ganambar who was a student at Dhupuma College in Gove NT remembers :

“I think we had to do three things that was happening at that time: one was the beginning, what they call the Dreamtime stories, the story of how life happened and that’s why I drew the two sisters down on the beach, and then the next one was what’s happening now, and the last one was what would you like to see in the future?”

Merrkiyawuy’s painting of a weeping brolga is one of 346 returned to Yirrkala Arts Centre from the National Museum of Australia, which has housed the artwork for the book since 1991. Dr Ian Coates, head of the Collections Development Team at NMA is quoted in that article as saying that the museum is working on digitising and repatriating originals back to artists in their communities. With 3383 illustrations from 70 schools Australia-wide, it would be a treat to see all of them repatriated to Country.

“Through the natural simplicity of their words and paintings, they convey their enjoyment and enthusiasm for the land which has been theirs for over 40, 000 years … the story of Australia revealed in this book reflects the poetry and imagination of the children who tell it. It speaks in a language that will be understood by children and adults throughout the world”– Book jacket copy.

This book was Highly Commended in the Picture Book category for the Children’s Book Council of Australia awards in 1978. There is a television film of the project (made at the same time) called ‘Dreamtime, this time dreamtime’ – described on Trove but not available online.

I’d always heard from teachers and family that I was, or should be, a writer. I was published in roneo’d school magazines and wrote letters to family and penpals incessantly. I once wrote a sensational teen novel in an exercise book that was passed around all my fellow Year 8 students, and disappeared in the process.

The only career path that anyone could suggest for a writer at that time was journalism. I had made the unfortunate choice to study politics in my Higher School Certificate year (Year 12) and that meant reading The Age from cover to cover each day. Not only did this cement my determination not to be a journalist, but I’ve avoided newspapers ever since. Except for their Books and Writing pages, of course.

Up until my final year of high school, I hadn’t known that a career being a children’s librarian was a thing. I write this now with many apologies to the anonymous custodians of programs and collections that I enjoyed at Te Takeretanga o Kura-hau-pō (Levin Library), Oakleigh Public Library and others. In 1977, I lived in Moorabbin and walked regularly to the library at the end of my street to earbash the excellent Margaret Aitken about my career ambitions. I began studying librarianship at RMIT that year, applied for the position of Assistant Children’s Librarian at St Kilda Public Library and began in earnest.

The State Library of Victoria hosted regular meetings for children’s library staff and at one of these I heard Margaret Dunkle talk about this book. It was the first time (but not the last) that I left a meeting with a book recommendation , walked straight to a bookshop, and bought it.

This book convinced me of the power of children’s own stories and artwork, forty years before I met and worked with Mary Tomsic while working for Kids’ Own Publishing – 2017 blog entry to come.

Note: Some of this text appears as an annotation in a database managed by the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature.